Ace Cafe to Everest base camp, with only 19 riders and a stuffed mouse for company

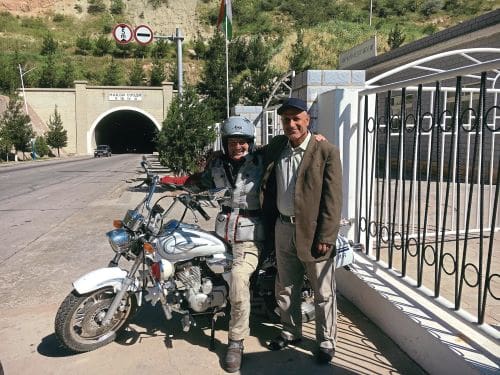

WORDS & PHOTOGRAPHY: Richard Barr

Since the age of 15, I have always enjoyed motorcycles. I started out in the 1970s on a Honda SS50, aged 16. Journeys were rarely more than 30 miles, but (perhaps with some rose-tinted hindsight) I enjoyed every minute of it. There will have been

wet, windy and freezing trips in sleet and snow – we lived in Scotland after all – but my recollections are more of the joy and the sense of achievement rather than the hardships.

Some 42 years after first venturing out on my SS50, I am sitting on my BMW GS1200 at the Ace Cafe in London, alongside 19 other adventure motorcyclists, and we’re about to ride to Mount Everest. That’s 10,000 miles, through 19 countries, in two-and-a-half months. I’m doing it for a very special reason.

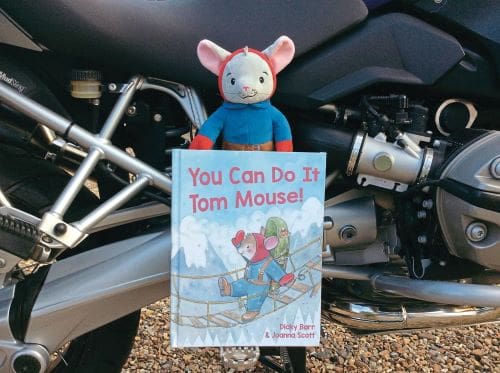

One person that shaped my life more than I could have imagined was our second son, Tom. He had Down’s Syndrome, and died in 2004 aged seven, in Great Ormond Street Hospital. Since then I have taken on a different challenge each year, raising funds for the Down’s Syndrome Association and Woolgrove School, a special needs academy. I’ve also embarked on a long-held dream, writing a series of children’s books to support the DSA. The first, You can Do It Tom Mouse! was launched at the end of 2018. Our Tom was of course the inspiration for the eponymous Mouse.

To ride to Everest you need a certain sort of bike, and my 2008 GS1200 fitted the bill. All right, it’s relatively old with 30,000 miles on the clock, but had been very reliable and I knew it well. Of course, it’s not perfect. The GS is no lightweight and is hugely outclassed by lighter, more agile machines in extreme off-road going. To tackle deep sand or thick mud on one of these, you need to have spent considerable time in the gym and/or have some good friends with you. I would find this out later on… On the other hand, lightweight machines tend to be less comfortable over distance. They feel under greater stress on long, fast tarmac roads and on intermediate surfaces. Given that most of our miles would be on surfaced roads, I felt that the GS was the best compromise.

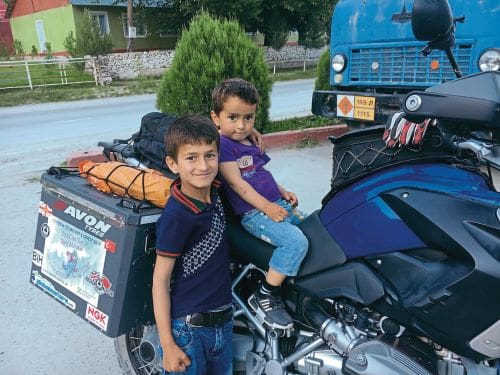

Obviously I’d need new tyres before we set off, and Avon Tyres are great supporters of the Down’s Syndrome Association. They kindly provided me with a set of TrailRiders which I used on the ride eastwards through Europe, and a set of TrekRiders for the rougher roads in Central Asia. Both sets were excellent and exceeded my expectations across a broad range of challenging conditions.

Business as usual

Our adventure was organised by GlobeBusters, recognised leaders in worldwide motorcycle expeditions, operated by the inspirational Guinness World Record Holders for long-distance motor-cycling, Kevin and Julia Sanders. Twenty riders from all over the world were taking part, plus three Globebusters guides.

The benefits of being part of an organised trip, rather than try and do it all on your own, soon became clear. Globebusters took care of the overall planning, navigating the necessary visa paperwork for rider and machine, in-country contacts, technical support and invaluable advice – after all, they had done this route several times before.

And although it’s an organised trip, most days you could if you wished spend all of your time riding on your own, drawing the daily briefings and comprehensive route notes, then meeting up with others in the evening. I loved this flexible approach – you were part of a group but also on your own adventure. Kevin would be in the Toyota pickup support vehicle, smiling and barking words of encouragement of which a favourite was… “It’s not a holiday, it’s an adventure!”

Having done all this before, Globebusters obviously had the route well worked out in advance. We would be heading through France, Germany, Austria, Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, Albania, Greece, Turkey, Georgia, Azerbaijan, across the Caspian Sea (by boat) to Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan and China, before arriving at Mount Everest base camp in Tibet.

Riding into central Europe on a motorcycle can and usually would be a fantastic adventure in itself, but our route down through Europe was a stepping stone towards where our adventure would really start: Istanbul and our gateway to Central Asia.

Leaving Europe

It was early in the morning as we crossed the border from Greece into Turkey – goodbye Europe, hello Asia. We had arrived early to avoid the queues, and it worked – everyone along with their bikes was processed and through within an hour. Turkey almost immediately felt different to the quiet and rural Greece we had left behind. You got the feeling this was a vibrant and ambitious country, something amplified hugely when we entered Istanbul, a city of over 15 million people, which straddles the Bosphorous river, bridging Europe and Asia.

Istanbul has a wealth of history and buildings, including the stunning Blue Mosque and the Hagia Sophia, which goes back to the 6th century. What captured me most, however, was the call to prayer. Five times a day the city would be alive with the call from hundreds of mosques. I found the call to prayer to be an emotional mix; somewhat haunting, moving, soothing, and conjuring ancient images of cultures largely unchanged through hundreds of years.

We caught the early-morning ferry across the Bosphorous and into Asia proper. Then it took us several days to ride across the vastness of central and eastern Turkey. Beautiful snow-capped mountains always seemed visible on our route, which at times took us within 100 miles of Iraq and Iran.

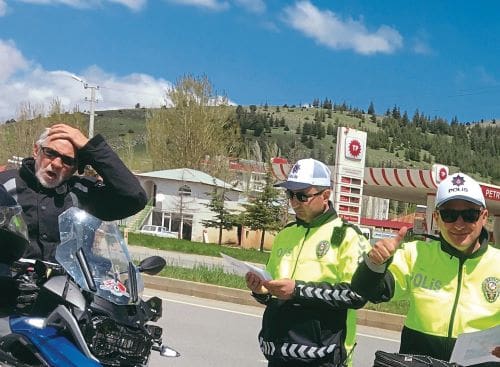

One feature of road travel across Turkey is the police speed traps and military checkpoints. I was stopped three times! In one encounter, I was the last in a group of four bikes when a radar trap led to all four of us being pulled over. After discussion amongst the police officers and reviewing their taped evidence they asked us our nationalities. Fines were then only given to the first two riders (both from the USA) and nationality bias did seem to play a part in whether you were fined or not.

They were then keen to have their photographs taken (complete with thumbs up) as they administered the penalty notices. Job satisfaction in the Turkish traffic police would appear to be high.

Getting out of Turkey wasn’t as quick as getting in and it took over four hours for all of us to get through the border into Georgia. It wasn’t down to queues, traffic or overworked staff, but rather that the immigration process was slow and not particularly evident. Our philosophy became, there is no point in getting frustrated with ‘delays’ at border crossings, or anywhere else for that matter. This is all part of the experience in adventure motorcycling. Just go with the flow, absorb and enjoy!

When we finally entered Georgia it was spectacular with a sweeping ribbon of tarmac high up into the mountains, and snow still piled up at the sides of the road – a few weeks earlier and the route would not have been so straightforward. As we travelled deeper into the country its beauty continued, but the pothole count increased significantly. Oh, and some of the Georgians’ driving was a bit erratic! Evidence of the country’s recent Soviet heritage was on show, with gas pipe networks running above ground in many of the towns, along with austere and dilapidated blocks of flats. This contrasted with the centre of the capital, Tbilisi, with its mix of modern and older architecture.

It was raining heavily as we approached the border with Azerbaijan, and a sign across the road which read ‘Azerbaijan Border – Good Luck’. Probably not the best strapline to encourage tourism. Azerbaijan felt different again to Georgia, initially with a number of painted statues and some castellated buildings which would not have looked out of place in Disneyland. We stopped briefly in Baku, the capital, which, like any large developing city, was busy and alive. But rather than stay, we headed on towards the local port – there was news that we might be able to get on a boat that evening to cross the Caspian Sea.

The ferry left Baku not to any schedule but rather when it was ready, which in this case was at midnight. The boat had some 20 lorries on board and along with our motorcycles the cargo area was full to capacity. A few of the riders got cabins, but for most of us it was a case of laying sleeping bags on the floor and dozing to the soothing and thrumming rhythm of the boat’s engines as it rolled gently on a smooth sea.

We arrived off Turkmenistan the next afternoon, but docking took a considerable amount of time into an immaculate new port, where the terminal was faced with what appeared to be gleaming white marble, a feature of many of the buildings in gas-rich Turkmenistan.

A convoluted customs process, albeit carried out by diligent and not unfriendly people, meant that we were not free to enter Turkmenistan until the early hours of the following morning. In some ways, I liked all the bits of paper we received, each carefully stamped. You don’t just wave a passport and walk into Turkmenistan, and it is a very unique place, as we would later find out. The secretive, controlling dictatorship of Turkmenistan, a country the size of Spain, reputedly allows only 10,000 tourists in each year. Averaging this out, with 20 of us, we represented about 10% of the tourist population for the week!

Finally free of customs, all stamped and in order, we rode 350 miles across part of the Karakum Desert (Black Desert) and to the capital, Ashgabat. We anticipated temperatures in the high 30s and having to keep fluid levels up, but as it transpired it was belting with rain for much of the journey, with spectacular lightning bolts arcing across the sky.

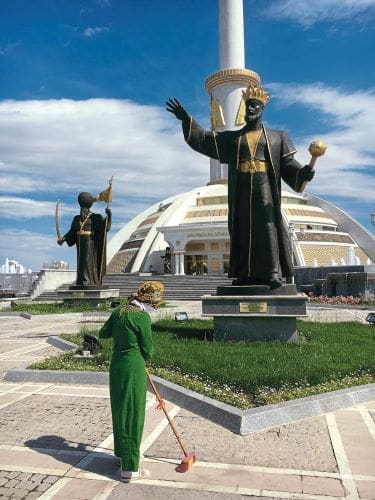

We had to leave our bikes outside the city, as our hotel was opposite the Presidential palace and foreign vehicles were precluded from the area. Turkmenistan is very sensitive about security and this included no pictures being permitted of the palace or at a number of other locations. No snaps were allowed either of the guards as they stood on ceremony outside the many government or public buildings. Even taking pictures in the local market was not allowed!

A bus tour of Ashgabat highlighted the massive investment in striking white marble buildings and tree-lined boulevards. Elaborate monuments, large blocks of pristine flats and trophy buildings, all seemingly trying to assert the country’s growing position, have been funded through its gas wealth. This included the world’s largest indoor ferris wheel, which somewhat defeats the purpose of a ferris wheel as a way of getting a clear view of the surrounding area.

What was really lacking was evidence of many people in this white, clean new world. Only later did we see the more authentic communities in flats and houses, which were largely from the Soviet era. I was left with a feeling of a city and indeed a country that sought recognition, but at the same time was struggling with itself as it demanded internal control and did not tolerate questioning.

We rode 150 miles north into the Karakum Desert, and set up camp just before the arrival of a huge storm. Later that night we went to see the stunning Darvaza gas crater.

Larger than a football pitch, this was formed after Soviet exploratory drilling for gas went wrong. Methane started to escape and so they set it alight, thinking that it would burn itself out in three to four weeks. That was in 1971, and it’s still going strong!

Make a Donation

A short video of the adventure can be found on the Tom Mouse website www.TomMouse.co.uk

Donations to either charity can be made through www.ChallengePictures.co.uk

Richard pays for all of his own costs and therefore all monies from donations go to the charities.