Words>Johnny Mac

Pics> Graeme Brown 2Snap / Mortons Archive

His third and final season in World Supersport was the 2008 one… and what a season that was. Andrew Pitt won his second world championship, Johnny Rea finished runner-up and switched to World Superbikes the following year, and Josh finished third in the final standings – but not without some controversy. Other contenders Broc Parkes, Fabien Foret and Joan Lascorz were all dispatched as Brookes made his breakthrough on the world stage, which ultimately got Honda on the phone to offer him a ride on the HM Plant Honda in BSB where he has been ever since.

Thirteen years, 305 race starts, 54 race wins, and two British Championship titles later… and of all the things I want to talk to him about, it’s the time he raced a little ol’ 600cc supersport bike he won a few races on some 14 years ago. While I was expecting and hoping to hear about hard racing, intense rivalries, and trick bikes, I got a lot more than I bargained for.

“In 2005 I won the Supersport and Superbike titles in Australia in the same season. I did that the whole time I was in Australia; I always rode both classes. I always thought that until you can beat everyone locally, why go around the world to get beaten by people when you can get beaten by people at home on your own doorstep? It seemed to me like a waste of time until I got to the point where I’d won both categories and I thought in my head that because I’d beaten everyone I could locally, I could justify making the step to world championship in 2006.

“I had some money in my pocket from the championship wins and sponsors so packed my bags and went overseas. I had an offer that was going to be a good possibility, with me and Max Neukirchner on Klaffi Honda in World Superbike, but at the last-minute Alex Barros lost his ride in GP’s and he came in with a load of Brazilian money, so Klaffi was like ‘this is a far better financial package’ and went with him instead. Obviously, Alex was a big name, so at the eleventh hour Max and I were dropped, so I started just riding for back of the grid teams in World Supersport.

“Some stuff happened there so I swapped to a WSB team, which was also back of the grid. There were lots of poor performances even though I was riding the best I could, learning the track on bikes that could barely score a point. It was a real struggle.

“Then the team I was in got bought by an Italian investor with all the promises in the world, but inevitably delivery wasn’t close to the promises. We started out okay but the previous team owner got shafted in the deal, so mid-season the guy stole the trucks from the team! He had more than one set of keys for the trucks, so in retaliation he showed up at a fuel station while everyone was inside eating lunch or something, jumped in and drove away in the trucks, just as a ‘f**k you’ back to the guy that shafted him. At this point the team couldn’t continue without the equipment that had been taken with the trucks, so the future was unknown – meaning I was free to end my contract without any penalty.

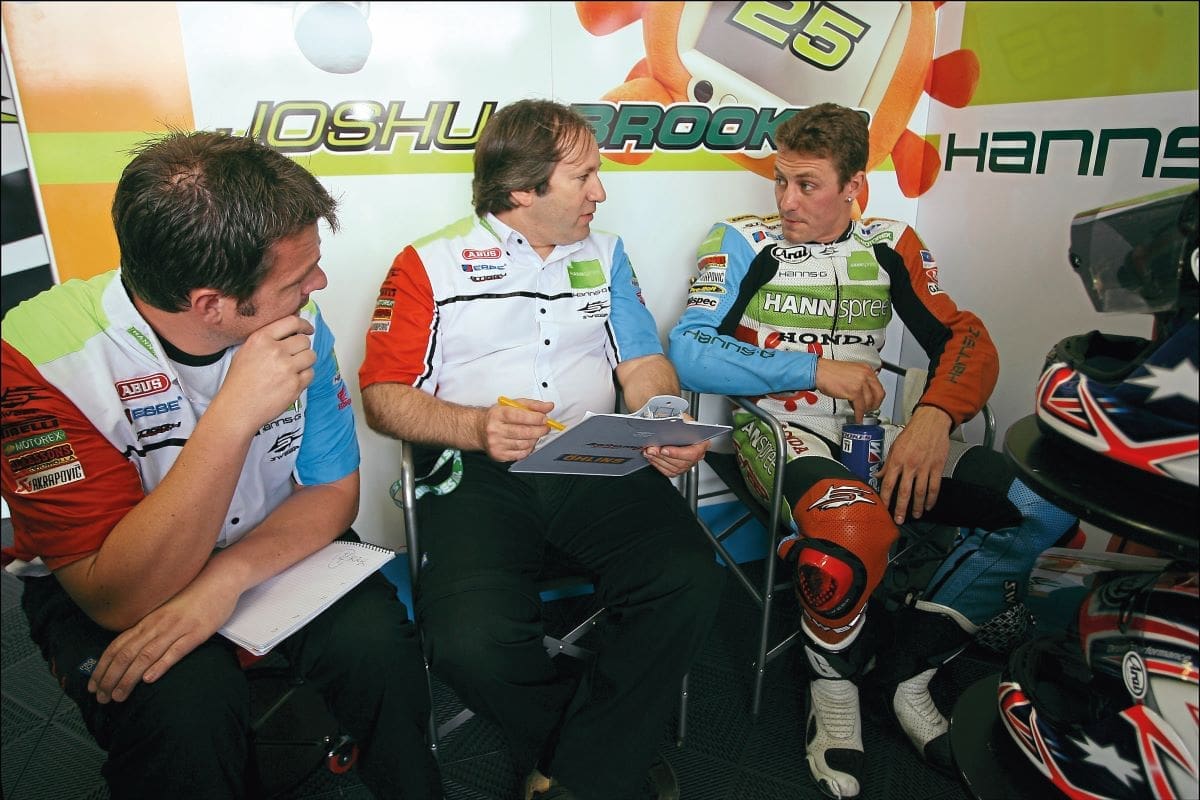

“I moved on and got a position at Stigefelt Honda team in World Supersport to finish the 2007 season, which put me in the prime seat to get a full season with Honda in 2008. The end of 2007 was sort-of the practice for 2008, a bit like a job interview.

“For 2008 my teammate was Robbin Harmes, and I got on with everyone in the team really well, which was nice after the turmoil I’d been through. It was a breath of fresh air and even though it wasn’t a top-level bike, it was a lot closer and much better compared to what I was used to. I won here in the UK at Donington and I got a second in Monza and Nürburgring and Philip Island, and a load of thirds. I had some fantastic races and great results, and as it turned out at the end of that year, it became controversial for me again.

“I had a 40,000 Euro championship bonus for second place and because Andrew Pitt had already won the championship, it meant that Johnny Rea couldn’t, and there was just one round to go. Rather than just circulate for second in the championship, Johnny made the switch to World Superbike for the last round to get ready for the following year because he was stepping into superbike in 2009 anyway. That meant with Johnny not there, all I had to do was finish in the top eight to get second in the championship, bearing in mind that the worst result I’d had all season was a fifth, so an eighth was really possible.

“I ended up eleventh with a totally shredded tyre. It felt like I was sabotaged in some way. The bike was horrible at that one meeting after being beautiful all year.

“Obviously, a lot of money would have had to be paid, which would have been justified for me but very inconvenient for them! As a result, we parted ways. I felt like I’d given the team all I had, and they had their best-ever results they’d ever had, and it was all was all so amicable and lovely right up to the point of the last round.

“It was lucky that we parted ways anyway, because I was being held to ransom that I didn’t have to be paid as much for the following year’s contract. However, the contract did hold me in it until a certain point in the year when there’s no rides available, so I hadn’t been looking.

“I was of the mindset that well, I’ve made it now, I’m top three in the championship against people like Andrew – who was twice world champion – and Johnny, who everyone already knew by then how good he is, so I felt like I was on the doorstep and that I’d done enough.

“But there weren’t any offers coming my way apart from the Honda one to come to BSB, so I said I’d take that option. I couldn’t get a quality ride or the respect I thought I deserved for the results I’d achieved that year, so I was happy to join Honda in BSB.

“The following year, 2009, Leon Haslam and John Hopkins rode for the team. I’m sure if you ask them, they’ll tell you it was the worst years of their careers – totally wasted. The team didn’t achieve, sponsors didn’t produce the money, bills weren’t paid, and parts weren’t received. It’s a slippery slope once you get to that point and it’s impossible to make progress.

“I feel like I dodged a bullet in a way, because after the years I’d already suffered working to get forward, to then have a year that could have been as bad as it looked like watching from the outside; that probably would have seen me pack my bags and go home to Australia for good.

“Supersport bikes were cutting-edge then. You had Suzuki, Kawasaki, Honda and Yamaha all pulling together and developing that supersport category because it was so important to them. Nowadays they’ve lost interest in that category because they’re not strong sellers on the road for some reason, which I don’t understand because 600s are brilliant, but they’re just not attractive now. It’s become unattractive for manufacturers to support and invest in the class for racing, so at the end of the day, as racers we are the ones who suffer because we miss out on such a good category.

“The bikes weren’t super trick, but they were all they could do and they were very evenly matched, so it was basically impossible to stretch your legs and get away at the front. They were all trying to build a bike within a sensible price range and be street legal, which sort of set the performance threshold, which meant the racing was really close – it was always a dog fight to the end.

“In the later years the races did stretch out; I think I just caught the tail end of when supersport was really good. It was even better in the years before I was there – you’d have 12 riders in a row, and there would be a snake of riders all trying to stay in the slipstream. By the time I was there, that group was maybe seven or eight in number, then a couple of years later it was just three or four at the front, so I kinda caught the last part of it.

“The rules in the category were very restrictive; supersport rules aren’t as open as superbike, for example, so the teams worked really, really hard to fine-tune every last bit that they were allowed to tune. They would have the fuelling different on each of the four cylinders because of the temperature given their proximity to the fairing. The inner two cylinders might be a bit hotter than the outer two, and the one with the cam chain next to it might have a different temperature to the one that doesn’t. They would rinse every last ounce out of it – they would even take the seals out of the wheel bearings so they would spin a little bit easier. It meant that they would have to replace the wheel bearings more regularly because they got more dust in them.

“The details and effort they went to in order to try and gain the tiniest advantage was amazing. We’d spend endless amounts of time trying to get a clutch setting to work better because we didn’t have engine braking control or auto-blippers. It was all old-fashioned; we were using the clutch lever and slipper settings to slow the bike down, so they were constantly trying to get better clutch settings. The bike itself wasn’t trick as such, but the level of attention, detail and ingenuity that went into how to make the most basic things the best that they can be was trick.

“The racing was hard and close, but there were never any nasty passes or anything that I would consider dirty. It was all hard, fast and close, and what I always expected racing to be, so it matched where I thought it should be as a kid growing up.

“I got labelled early on in my career by my mechanics and teams as a supersport rider, but I guess your personal objectives and goals might not suit what others think you’re suited to.

“I always wanted to be at the cutting edge. As a kid I wanted to race the 500s in GPs; I didn’t just want sit in the support class – I wanted to get to the top, and I wanted to get there yesterday, so I went to superbike at every opportunity. Even when I was racing both classes in Australia, if I was leading the supersport championship and was something like fifth in superbike and someone said ‘You’ve got to give up one of the bikes for the remainder of the year’, I’d have given up the supersport bike, even if I had a chance of winning the championship on it. I was obsessed that it had to be SBK.

“That said, I think I suited the bike and the category well, and when I got a competitive bike, it was a lot of fun. I was on a bike that was capable of running at the front and that’s the bit that stands out. To be able to ride at the maximum of your own ability and the bike’s ability is brilliant.

“I think about those days more fondly now than I probably did at the time. Back then it felt like I was treading water, you know, like there was somewhere else I needed to be in life. Everything felt like it was getting delayed. I wanted to be in GPs, and it had already changed from two-stroke to four-stroke, so in my mind it was moving on without me. I feel like I was trying to push things into an area where I thought they should be, and politics were holding me back and opportunities weren’t opening for me, while other riders – who, from where I was standing, I felt I was riding at least as good if not better than – were getting the rides and opportunities. I spent a lot of that time feeling angry, but now that I can look back on it, it’s worked out all right and I’m actually quite fond of those times racing around the world.

“That said, even though I was 23 or 24 years old, I missed home. I was on my own, trying to make it in Europe and up to that point working for Italian teams, which was chaotic. The beauty of the Swedes in 2008 was they all spoke English; their grammar and punctuation was better than mine! It was nice to be around people who spoke perfect English because I felt like I was in such a whirlwind, trying to find my feet, living out of a camper and going from round to round and not really knowing what to do with the week in between. It was traumatic in some ways but it’s what shapes us. I wouldn’t take any of it back. It made me determined.

“I’ll never know if the choices I made were right but the path I’ve ended up on has been great; I wouldn’t have done the TT if I hadn’t come to BSB, and I’ve done fantastic things.

“Hindsight is a wonderful thing, but if I could go back and speak to my 23-year-old self, I’d say there’s no rush. I wanted to be somewhere else, somewhere that I thought was better. I would tell myself to take three years if that’s what it needs. Then, three years felt like a lifetime, but now, I’d say if there’s a three-year contract there, take it for the continuity and the chance to prove yourself thoroughly. I wonder if some of the decisions I made were because they were the only options on the table, so I don’t know if the advice would really make a difference! The mindset was to get there fast.”